SEO Summary:

- Post-meal blood sugar spikes (postprandial hyperglycemia) cause chronic inflammation and are a key driver of insulin resistance and vascular damage.

- A short, targeted walk after eating can be more effective at reducing these spikes than sitting, due to a unique mechanism: activating muscle cells to absorb circulating glucose without needing insulin.

- This effect is maximized when the walk is a precise moderate intensity—a brisk pace that makes talking slightly effortful—not a leisurely stroll.

- Click to learn the 10-minute protocol, the science of glucose uptake, and the specific pace required to stabilize your blood sugar immediately after eating.

The Post-Meal Problem: The Dangerous Glucose Spike

We have become accustomed to the heavy, sleepy feeling that often follows a large meal, especially lunch or dinner. This feeling is not just the body dedicating energy to digestion; it’s a clear sign of Postprandial Hyperglycemia—a sharp, high spike in blood glucose.

Why Spikes Are More Dangerous Than Averages

While doctors often focus on A1C (which measures average blood sugar over three months), the variability and height of your post-meal spikes are often the most damaging factors to your long-term health:

- Vascular Damage: High, sudden surges of glucose are corrosive to the delicate lining of your blood vessels (endothelium). This chronic damage accelerates atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), increasing the risk of heart disease and stroke.

- Insulin Overload: Frequent spikes force the pancreas to work overtime, releasing massive amounts of insulin. This eventually leads to Insulin Resistance, where cells become deaf to the hormone’s signal, leading directly to Type 2 Diabetes.

- Inflammation: Glucose spikes increase oxidative stress and inflammation, accelerating the aging process throughout the body.

The good news is that we have an immediate, non-pharmacological tool to flatten these spikes and prevent this cellular damage: a short, timed walk.

The Blood Sugar Slump: Signs You Need a Post-Meal Walk

If you don’t feel acutely diabetic, it can be hard to know if your post-meal response is healthy or harmful. The body, however, provides clear warning signals that the glucose spike is too high and too fast.

Common Signs of Postprandial Dysfunction

- Immediate Sleepiness/Fatigue (The Slump): A high glucose spike is often followed by a rapid, over-correction by insulin, leading to a quick drop in blood sugar (reactive hypoglycemia). This crash causes profound fatigue, brain fog, and the strong urge to nap after eating.

- Increased Hunger After Eating: If you feel hungry again an hour or two after a large meal, it’s a sign that the body over-released insulin and “crashed” your blood sugar, signaling a need for more food.

- Brain Fog and Difficulty Concentrating: High blood sugar is toxic to brain function. The difficulty in focusing immediately after a meal is often a direct result of the spike.

- Excessive Thirst and Urination: While often associated with full-blown diabetes, these are immediate signs that the kidneys are trying to dump excess glucose from the bloodstream.

If you experience the post-lunch slump or the post-dinner drowsiness, your body is begging for a quick way to clear the circulating sugar.

The Glucose Clearance Secret: Why Timing is Everything

The power of the post-meal walk is rooted in a fascinating physiological mechanism that bypasses the body’s reliance on insulin.

The GLUT-4 Gateway

Muscle cells are the body’s largest glucose storage compartments. When you eat, insulin signals the muscle cells to open up specialized gateways called GLUT-4 transporters to take in the glucose circulating in the blood.

However, when you engage your muscles through exercise, something extraordinary happens:

- Insulin-Independent Uptake: Muscle contraction itself forces the GLUT-4 transporters to move to the cell surface and open the gates, allowing glucose to flood into the muscle without needing an insulin signal.

- The Glucose Sponge: In this state, your muscles act as a highly effective “glucose sponge,” quickly vacuuming up the excess sugar from the bloodstream right when it is peaking, thereby flattening the post-meal spike.

The key is timing. This effect is maximized immediately after eating, when blood glucose concentrations are highest. Studies have shown that a walk taken 30–60 minutes after a meal is dramatically more effective at lowering blood sugar than the same walk taken an hour later or earlier in the day.

The 10-Minute Post-Meal Protocol: Finding Your Sweet Spot Pace

The difference between a successful, spike-flattening walk and a nice, but ineffective, stroll comes down to the intensity of the movement.

To force the muscles to utilize the insulin-independent GLUT-4 mechanism, your muscles must be contracting with purpose.

The Advocate’s Blood Sugar Walk Checklist

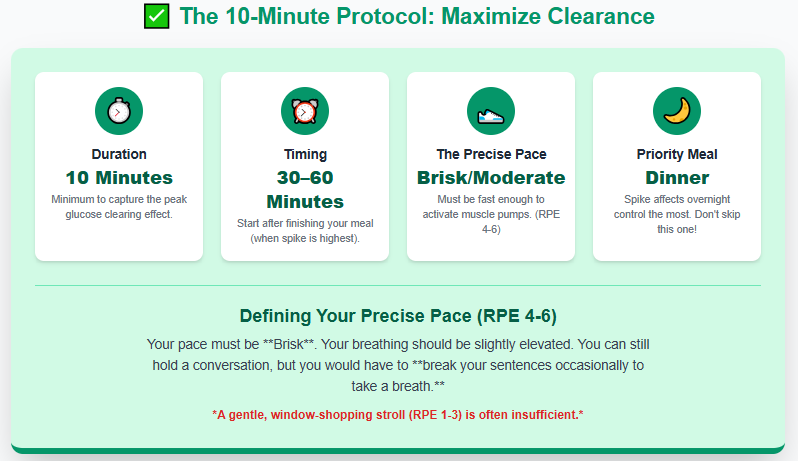

| Component | Protocol Detail | Rationale |

| Duration | 10 Minutes minimum. | Short enough to be sustainable daily; long enough to capture the peak glucose clearing effect. |

| Timing | Start 30–60 minutes after finishing your meal. | This is the window where the glucose spike is highest and the muscle uptake is maximized. |

| The Precise Pace | Brisk/Moderate Intensity (RPE 4-6/10). | The pace must be fast enough to activate the muscle pumps, requiring effort but not exhaustion. |

| Priority Meal | Focus intensely on the walk after Dinner. | Dinner is usually the largest meal and its resulting spike affects overnight glucose control the most. |

Defining the Precise Pace

The mistake most people make is taking a gentle, window-shopping stroll. While relaxing, this is often insufficient to trigger the insulin-independent muscle uptake.

Your pace must be Brisk—an intensity that you would rate as a 4 to 6 out of 10 on the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale.

- RPE 4-6: You are moving fast enough that your breathing is slightly elevated. You can still hold a conversation, but you would have to break your sentences occasionally to take a breath.

- Not RPE 1-3: You are not just moseying. You are moving with purpose, and your heart rate is slightly elevated.

This sustained, brisk movement creates the necessary muscle contraction to open those GLUT-4 gates and pull the glucose out of your blood, delivering the maximum spike-flattening effect.

Beyond the Walk: Lifestyle Integration for Insulin Sensitivity

While the 10-minute walk is a powerful acute intervention, lasting glucose control and insulin sensitivity require a broader strategy that builds your muscles into better glucose storage units.

Strategies for Long-Term Glucose Control

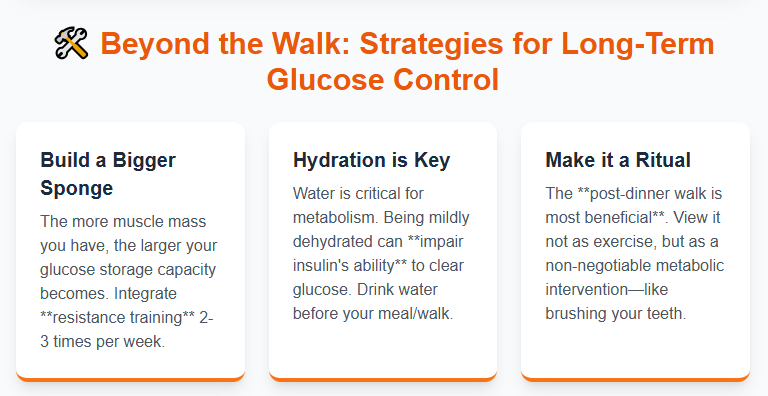

- Prioritize Resistance Training: The more muscle mass you have, the larger the glucose “sponge” becomes. Integrating resistance training (weights, bodyweight, resistance bands) 2-3 times per week builds more storage capacity, improving your glucose tolerance 24/7.

- Hydration is Key: Water is critical for every metabolic process. Being even mildly dehydrated can impair insulin’s ability to clear glucose. Ensure you are well-hydrated before and during your walk.

- The Dinner Walk is Essential: Because the dinner meal is often the heaviest in carbohydrates and the subsequent glucose spike is not mitigated by standing or moving (as often happens after breakfast/lunch), the post-dinner walk is arguably the most beneficial 10 minutes of exercise you can do all day for better overnight glucose control.

My Personal Advice as a Health Advocate

I know what you are thinking: “I’m tired after dinner, and I don’t have time.”

The beauty of the 10-minute walk is its sustainability. It is not an intense workout; it’s a non-negotiable metabolic intervention. Instead of viewing it as exercise, view it as part of your meal, like brushing your teeth after eating.

My advice is to make the walk a ritual tied to dinner. Get the family involved, listen to a short podcast, or simply use those 10 minutes as a transition between the busyness of the day and the quiet of the evening. The slight effort of the brisk pace is a tiny investment that pays massive dividends in mood stabilization, sustained energy, and long-term vascular health. Don’t skip it; your blood vessels are counting on you.

Myths vs. Facts: Walking and Metabolism Misconceptions

The power of walking for metabolic health is often underestimated.

| Myth | Fact |

| Myth: Walking is too gentle to have a real metabolic effect. | Fact: Walking at a brisk pace triggers the insulin-independent GLUT-4 mechanism, providing an immediate, powerful effect on clearing blood glucose. |

| Myth: You must walk for at least 30 minutes to burn fat. | Fact: While longer walks are great for fat burning, the glucose-clearing effect we are targeting is maxed out in the first 10-15 minutes immediately after the meal. |

| Myth: Walking can replace diabetes medication. | Fact: NO. Walking is a powerful complementary tool. Never stop or change prescribed medication without strict doctor supervision. The studies show it can outperform sitting, but it is not a cure. |

| Myth: It doesn’t matter when I walk, as long as I get my steps in. | Fact: Timing is critical for the glucose-clearing effect. The walk must be close to the blood sugar peak (30–60 minutes post-meal) to maximize the uptake. |

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- What is RPE and how do I measure it?RPE stands for Rate of Perceived Exertion (on a scale of 1 to 10). RPE 1 is sitting; RPE 10 is an all-out sprint. Your goal is RPE 4–6: you feel like you are working, but you are not struggling for breath.

- Can I use a treadmill instead?Absolutely. A treadmill is a highly consistent way to ensure you maintain the precise pace needed (RPE 4-6). Setting a slight incline can also increase the muscle contraction and glucose uptake.

- Should I walk after every meal?Yes, the benefits are dose-dependent. A walk after breakfast, lunch, and dinner will provide the highest level of glucose stabilization, though the dinner walk is the most critical.

- Does the walk have to be exactly 10 minutes?Ten minutes is the researched minimum to capture the full effect, making it highly sustainable. If you can do 15 or 20 minutes, even better, but the critical benefit occurs in that first 10 minutes of brisk movement.

- Does the post-meal walk also help with digestion?Yes. Gentle movement increases blood flow to the digestive tract and stimulates intestinal motility, reducing sluggishness and bloating.

Conclusion & A Final Word of Encouragement

The simple 10-minute post-meal walk is a marvel of human physiology—a profound, non-pharmacological intervention that instantly taps into your muscle cells’ ability to regulate blood sugar.

The critical insight is the precise pace. It must be brisk enough to engage the muscles and open those GLUT-4 gates, transforming your walk from a leisurely stroll into an immediate, powerful metabolic fix.

Commit to this simple, 10-minute brisk walk after dinner tonight. Flatten that glucose spike, stabilize your energy, and take the single most powerful step you can for your long-term cardiovascular and metabolic health.

Disclaimer: I am a health advocate and writer, not a medical doctor. The information in this article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Consult your physician, especially if you are diabetic or taking glucose-lowering medication, before starting any new exercise regimen.