We are all taught that iron is an essential mineral, the heroic component of hemoglobin responsible for carrying life-giving oxygen through our blood. Iron deficiency—anemia—is rightly recognized as a health risk, leading to fatigue and weakness.

However, in the context of modern Western diets, high consumption of red meat, iron-fortified foods, and even genetic predispositions, a quiet and insidious problem is becoming increasingly relevant, particularly for adult men and post-menopausal women: iron overload.

Too much iron, even levels considered “high-normal,” can act as a metabolic saboteur within the body, triggering a relentless cascade of cellular damage that accelerates the aging process. It’s not about deficiency; it’s about a dangerous excess that many people unknowingly carry. For these individuals, the focus needs to shift from getting enough iron to safely managing its abundance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjowKsrxBC8

💡 The Chemistry of Aging: Excess Iron and Oxidative Stress

Iron’s biological superpower is its ability to easily swap electrons, transitioning between the ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) states. This is what makes it so brilliant at transporting oxygen.

Unfortunately, this same chemical property makes unbound, free iron a catalyst for cellular destruction.

The Fenton Reaction: The Source of Damage

When iron is in excess, it can participate in the infamous Fenton Reaction, a chemical process that takes place inside your cells:

Fe2++H2O2→Fe3++OH⋅+OH−

In simple terms, free iron reacts with hydrogen peroxide (a normal byproduct of metabolism) to create the hydroxyl radical (OH⋅). This hydroxyl radical is the most reactive and damaging free radical known to biology. [Image showing the Fenton reaction with Fe2+ catalyzing the creation of the highly reactive hydroxyl radical]

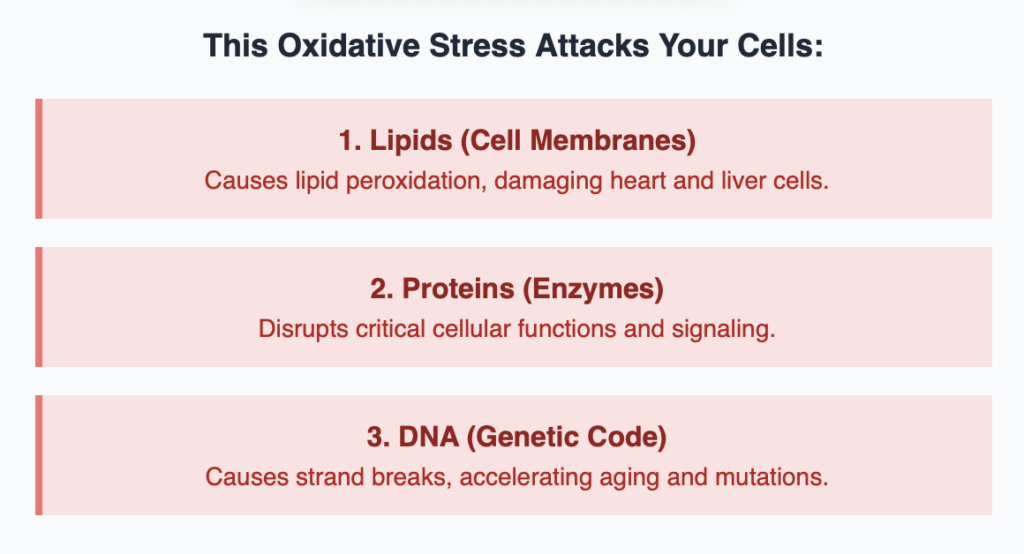

This rampant free radical production is known as oxidative stress. It doesn’t just cause minor wear and tear; it directly attacks and damages:

- Lipids: Leading to lipid peroxidation (damaging cell membranes, particularly in the heart and liver).

- Proteins: Disrupting enzyme function and cellular signaling.

- DNA: Causing DNA strand breaks, which increases the risk of mutations and accelerates cellular aging and senescence.

This destructive process is so fundamental to the cell that high iron accumulation has been implicated in a specific form of regulated cell death called ferroptosis.

🧠 The Overlooked Driver of Inflammation and Organ Damage

Oxidative stress is the direct precursor to chronic, low-grade inflammation, which is the hallmark of nearly all age-related chronic diseases.

Iron’s Attack on Critical Organs

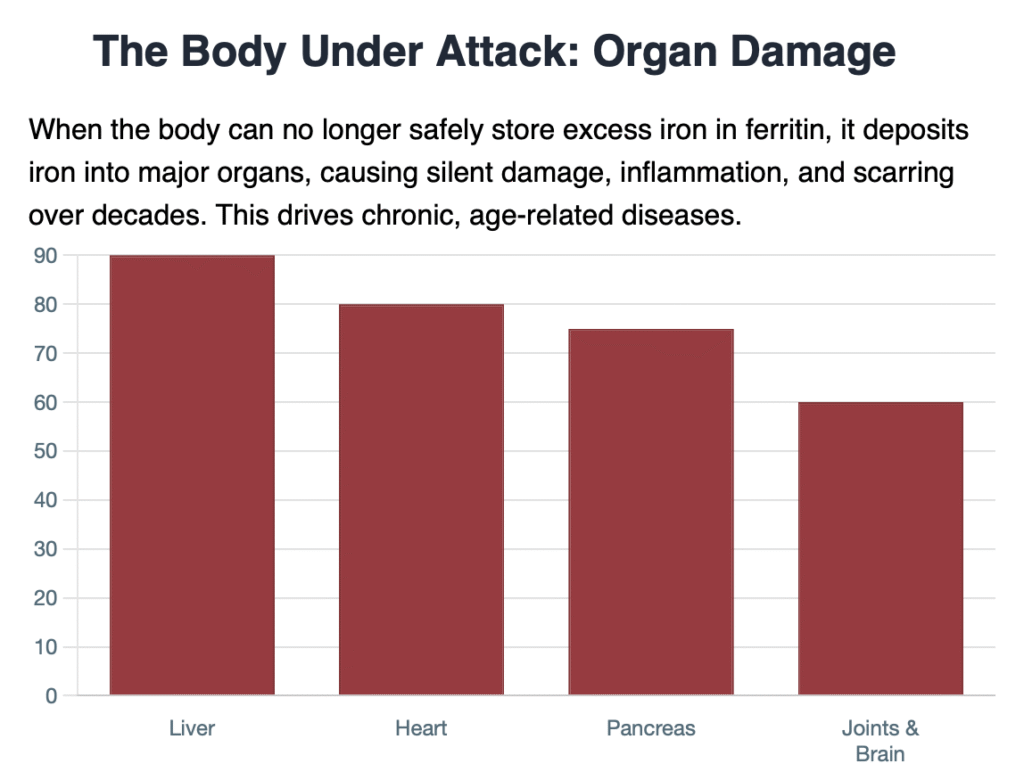

When the body can no longer safely store the excess iron (primarily in the storage protein, ferritin), the iron is deposited into major organs, causing progressive, silent damage over decades. This is most evident in the genetic condition Hereditary Hemochromatosis, but similar, subclinical accumulation can affect many adults:

- Cardiovascular System: Iron deposits in the heart can affect its ability to circulate blood effectively, leading to cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure. High serum ferritin levels have also been independently associated with the presence of coronary artery calcium (CACS), a marker of early atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk.

- Liver: The liver is the main storage site. Excess iron causes chronic inflammation and scarring, leading to cirrhosisand increasing the risk of liver cancer.

- Pancreas: Iron accumulation damages the insulin-producing islet cells, significantly raising the risk of Type 2 Diabetes (often referred to in this context as “bronze diabetes” due to the skin discoloration iron can cause).

- Joints and Brain: Iron deposits in the joints lead to arthritis, and its accumulation in certain brain regions is increasingly linked to neurodegenerative diseases.

The connection is clear: High iron status—often measurable through elevated serum ferritin—is not just a consequence of disease, but a measurable risk factor that actively drives chronic inflammation, arterial damage, and the overall progression of biological aging.

The Gender Paradox: Why Iron Levels Differ

The observation that men generally have a shorter lifespan than women, particularly before menopause, has long been a subject of research. A compelling hypothesis suggests that differences in iron status play a contributing role:

- Pre-Menopause Women: Due to regular menstrual cycles, women naturally engage in a form of bloodletting, which is the most efficient way to excrete excess iron from the body. This protective mechanism generally keeps their iron stores low.

- Men and Post-Menopause Women: Without this regular iron loss mechanism, iron tends to accumulate progressively over decades. This accumulation begins after age 40 in men and often accelerates in women after menopause.

For most adults who are not menstruating, the body has no built-in, specialized mechanism to excrete excess iron, making dietary and lifestyle management critical.

👀 A Simple At-Home Practice: The Iron-Lowering Method

If lab results confirm that your iron stores (specifically your ferritin level) are elevated, the most direct and medically proven treatment for iron overload is therapeutic phlebotomy (blood donation/blood draw), performed under a doctor’s supervision.

However, for those with mild or moderate elevation, or as a powerful complementary strategy, there are several effective, safe, and simple at-home practices centered on diet and lifestyle:

1. The Power of Blood Donation

If you are generally healthy and eligible, regularly donating blood is the most effective and safest non-medical way to lower your iron stores.

- Mechanism: Every pint of blood donated removes approximately 200–250 mg of iron from the body.

- The Practice: If your doctor agrees, becoming a regular blood donor (every 8 to 12 weeks) can serve as an excellent maintenance treatment to keep iron levels in check.

2. Strategic Dietary Adjustments

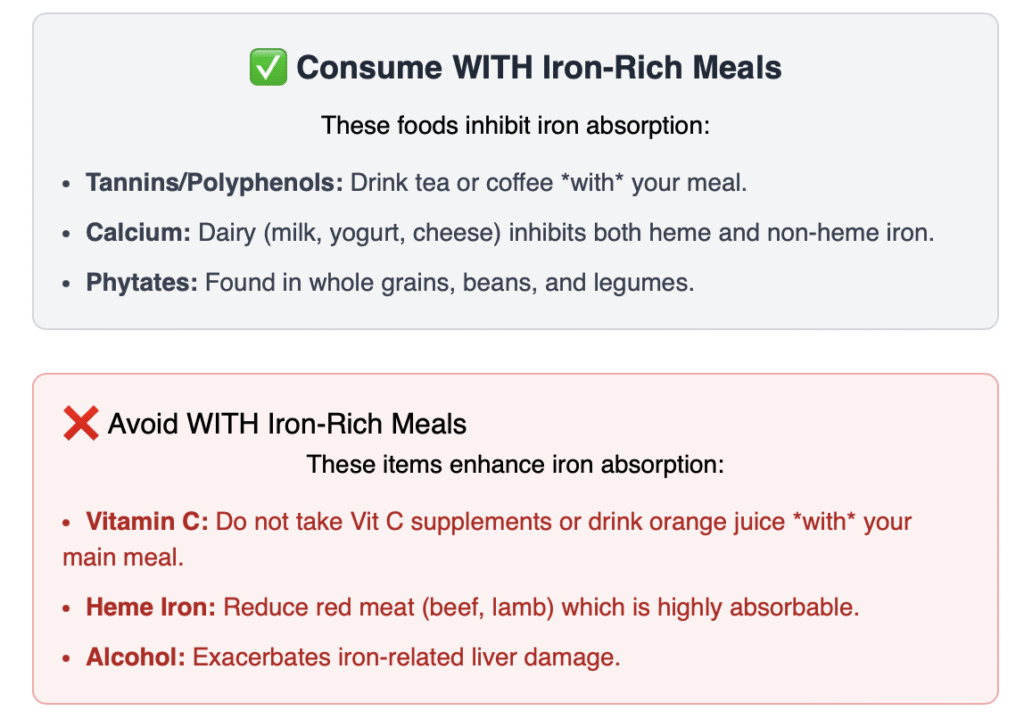

Since the body’s control over iron is managed primarily by absorption, strategic dietary changes focus on inhibiting the absorption of iron consumed in meals.

| Category | Action | Specific Foods/Timing |

| Heme Iron Reduction | Limit the most absorbable form of iron. | Reduce Red Meat and Organ Meats. Heme iron, found only in animal products (especially beef, lamb, and liver), is absorbed far more efficiently (15-35%) than non-heme iron (2-20%). |

| Iron-Blocking Foods | Includecompounds that bind to iron. | Tannins and Polyphenols: Drink Tea or Coffee with meals. The tannins and polyphenols in these beverages can inhibit non-heme iron absorption by up to 60-90%. |

| Calcium-Rich Foods: Consume Dairy (milk, yogurt, cheese) with iron-rich meals. Calcium is the only known substance that inhibits the absorption of both heme and non-heme iron. | ||

| Phytates (from Whole Grains/Legumes): Phytates in whole grains, beans, and lentils bind to iron, reducing its uptake. | ||

| Vitamin C Timing | Avoid enhancers of absorption. | Do NOT take Vitamin C supplements or eat very high Vitamin C foods (e.g., orange juice) with your main iron-rich meal, as Vitamin C drastically enhances iron absorption. |

| Avoid Alcohol | Reduce liver strain. | Limit or avoid alcohol, as it exacerbates iron-related liver damage. |

3. Smart Supplementation

If your ferritin is high, you must stop taking any supplements that contain iron, including most standard multivitamins and B-complex vitamins. Furthermore, be cautious of taking Zinc or Magnesium supplements at a different time than iron-rich meals, as these minerals compete with iron for absorption, and may help modulate its uptake.

⏳ The 2-Minute Read Takeaway

While iron is essential for life, the silent reality for many adults is that too much iron is pro-aging and pro-inflammatory. Through the Fenton Reaction, excess iron catalyzes the formation of highly destructive free radicals that relentlessly damage cellular structures, leading to the chronic inflammation associated with heart disease, diabetes, and neurodegeneration.

The solution is not complex, but it requires awareness and action:

- Get Tested: Ask your doctor for a Serum Ferritin test to know your iron storage status.

- Act Strategically: If your ferritin is elevated, stop iron supplements and use the at-home methods—especially regular blood donation (if eligible) and the strategic pairing of iron-blocking foods (tea, coffee, calcium, legumes) with iron-rich meals.

By managing your iron, you are not just treating a number; you are actively removing one of the most potent internal drivers of oxidative stress, thereby slowing down the biological clock and protecting your vital organs.