In a world obsessed with calorie counting, macronutrient ratios, and the glycemic index, we often overlook the most fundamental, oldest step in digestion: chewing. It’s a seemingly mundane act—a reflex we perform thousands of times a day—yet emerging research is revealing it to be one of the most powerful, non-pharmacological tools we have for controlling our post-meal blood sugar.

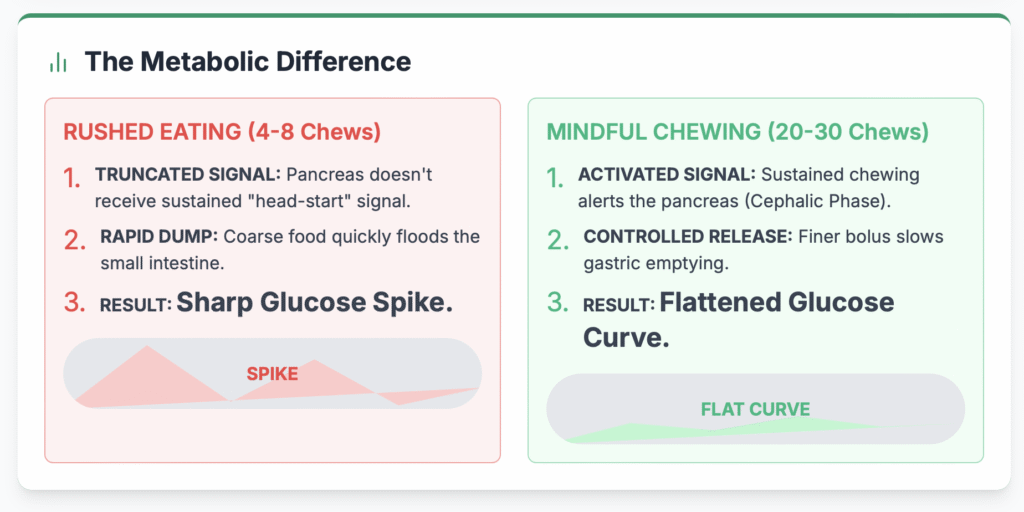

We’ve been taught that digestion begins in the stomach, but the truth is, the crucial first signals that dictate your body’s metabolic response start the very moment your teeth touch food. This initial phase, often completed with a hasty four to eight chews, is a hidden orchestration of mechanical breakdown and enzymatic signaling. Fail to give it due attention, and you set yourself up for a sharp, unhealthy glucose spike.

The promise is simple: by changing how you eat, not just what you eat, you can significantly alter your metabolic destiny.

🔬 The Hidden Orchestration: Chewing as a Pre-Digestive Signal

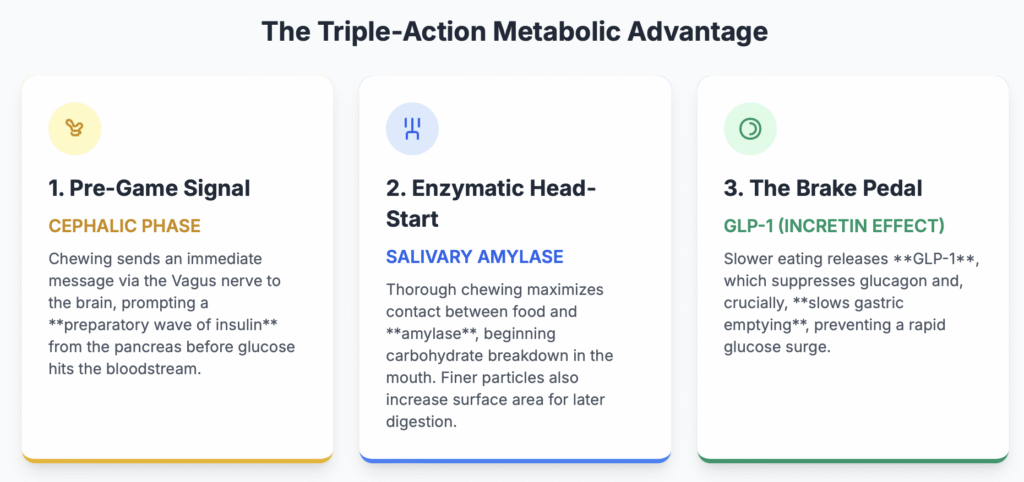

To understand the profound impact of chewing, we must first appreciate the “cephalic phase” of digestion—a fascinating, Pavlovian response that prepares your entire system for the incoming meal.

The moment food enters your mouth, the process is no longer just about grinding solids into a swallowable bolus. The sensory experience—the sight, smell, and most importantly, the mechanical action of mastication—sends an immediate, urgent message via the vagus nerve directly to the brain. This is a head-start signal, a metabolic pre-game, that is often rushed and ignored.

When this signal is adequately sustained through prolonged chewing, the brain relays the message to the pancreas. In a healthy response, the pancreas begins to secrete a small, preparatory wave of insulin even before the glucose from the food has been absorbed into the bloodstream.

The Problem with Hasty Eating

When we rush, taking the typical 4-8 chews before swallowing, this crucial cephalic phase is truncated. The pancreas doesn’t receive the sustained warning it needs. The food is then quickly dumped into the stomach and small intestine, where carbohydrates are rapidly broken down into glucose. This glucose floods the bloodstream in a rush, leading to the characteristic post-meal blood sugar spike.

The pancreas, belatedly scrambling to catch up, then overcompensates, leading to an excessive insulin release. Over time, this rollercoaster of high glucose spikes and high insulin demands can contribute to insulin resistance, a cornerstone of Type 2 Diabetes and chronic metabolic dysfunction. The mechanical act of chewing, therefore, is not merely about size reduction; it’s about synchronizing your body’s hormone response with the arrival of nutrients.

🧪 The Salivary Secret Weapon: Amylase and the Pancreas

The mouth is home to a powerhouse enzyme: salivary amylase. Amylase is the enzyme specifically tasked with breaking down starch (a complex carbohydrate) into smaller, more digestible sugar molecules. It is the first stage of carbohydrate digestion.

However, amylase requires time and thorough mixing to do its job. When you chew a starchy food—like rice, bread, or a potato—the mechanical action breaks the food into smaller particles, increasing its surface area. Simultaneously, prolonged chewing stimulates the release of abundant saliva, ensuring maximum contact between the food and the amylase.

The Mechanical Breakdown Multiplier

- Increased Surface Area: Finer particles expose more surface area for digestive enzymes in the stomach and small intestine to act upon later.

- Amylase Pre-Digestion: The initial carbohydrate breakdown in the mouth lessens the digestive burden downstream.

- The Viscosity Factor: The goal of chewing is to turn food into a near-liquid slurry, or bolus. This softer, finer bolus is easier for the stomach to process and allows for a more controlled, slower release of glucose into the small intestine, further contributing to a flatter glucose curve.

A 2013 study published in the Endocrinology Journal and subsequent research have explored the effects of chewing on postprandial glucose. While results can vary between healthy individuals and those with existing dysglycemia, the underlying mechanism is consistent: thorough mastication supports a more efficient, prepared metabolic response.

🧠 The Gut-Brain Axis: Satiety and the Incretin Effect

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWg84GKZYbA

The benefits of extended chewing stretch far beyond the initial blood sugar signal; they involve the entire gut-brain axis, particularly the complex system of satiety hormones.

Chewing longer is intrinsically linked to eating slower. When you slow down your eating rate, you give your digestive tract the crucial 20 minutes it takes to release satiety-signaling hormones. Among the most important are the incretin hormones, such as Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1).

The GLP-1 Connection

GLP-1 is a key hormone secreted from the small intestine in response to nutrient presence. Its effects are manifold and directly beneficial to metabolic health:

- Stimulates Insulin Secretion: GLP-1 enhances the insulin-secreting response from the pancreas.

- Suppresses Glucagon: It inhibits the release of glucagon, a hormone that raises blood sugar, effectively putting a brake on excess glucose production by the liver.

- Slows Gastric Emptying: Crucially, it slows the rate at which food leaves the stomach, preventing a rapid flood of glucose into the small intestine. This is arguably the most powerful mechanism for flattening the glucose spike.

- Promotes Satiety: It signals fullness to the brain (hypothalamus), leading to decreased overall food intake.

Studies have shown that prolonged chewing can increase GLP-1 secretion. By taking the time to fully process a bite, you are essentially providing the ideal conditions for these metabolic master regulators to be released and act on your system. This leads to better blood sugar control and, critically, a reduction in total caloric intake due to enhanced feelings of fullness.

📈 The Scientific Evidence: From Lab to Plate

The idea of meticulous chewing—sometimes called “Fletchering” after the American nutritionist Horace Fletcher—is not new, but modern science is now providing concrete evidence for its metabolic benefit.

Several interventional studies have compared the effects of “routine” vs. “thorough” mastication on post-meal blood glucose levels:

- Reduced Postprandial Glucose: One study comparing 20 chews per mouthful to 40 chews per mouthful found that while overall blood glucose levels didn’t change drastically in all groups, the more thorough chewing led to a significantly lower postprandial blood glucose concentration in normoglycemic (non-diabetic) individuals. This reduction is attributed to a stronger early-phase insulin response—the preparedness signal.

- The Dental Health Link: Perhaps the most compelling, real-world evidence comes from studies linking poor occlusal function (inability to chew properly due to missing or damaged teeth) to higher HbA1c (average long-term blood glucose) levels in patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Patients who had their chewing function restored through dental work showed significant improvements in their blood sugar control. This suggests that the physical ability to chew well is a non-negotiable prerequisite for optimal metabolic health.

- Eating Rate and Obesity: A wealth of epidemiological research consistently links a faster eating rate with increased energy intake, higher BMI, and an elevated risk for developing Type 2 Diabetes. Chewing longer is the most direct way to reduce your eating rate. By doubling the number of chews, participants in some satiety studies consumed significantly less food while reporting the same level of satisfaction. This dual benefit—better glucose control and reduced calorie intake—makes prolonged chewing a powerhouse intervention.

👀 Beyond the Eight: Unveiling Your Optimal Chewing Count

The core question remains: If the typical person chews a mere 4-8 times, how many times should we be chewing?

The classic advice, popularized by Horace Fletcher, was 32 chews per bite. While this is an excellent target for awareness, the scientific consensus is that there is no single, magic number for every food. You don’t need to chew a watermelon slice 32 times, but you certainly need more than 8 chews for a piece of steak or a handful of almonds.

The Simple, Actionable Goal

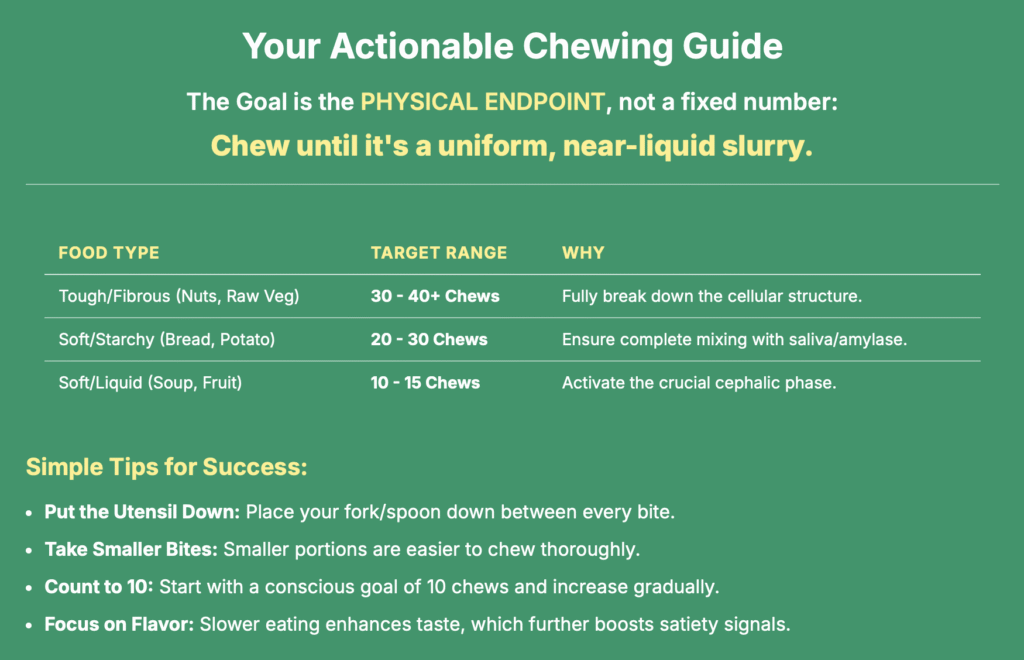

The key is to shift your focus from a fixed number to a physical endpoint.

The goal is to chew each bite until it reaches a uniform, near-liquid or mushy consistency that is almost indistinguishable from the saliva in your mouth.

| Food Category | Recommended Chews/Bite (Approximate) | The Goal |

| Tough/Fibrous (Steak, Raw Vegetables, Nuts) | 30 – 40+ | A uniform, easily swallowed paste, ensuring the food’s cellular structure is fully broken down. |

| Soft/Starchy (Bread, Pasta, Potatoes) | 20 – 30 | The food fully dissolves, mixing completely with saliva until it feels like a liquid slurry. |

| Soft/Liquid (Soup, Yogurt, Fruit) | 10 – 15 | Take the time to “chew” to stimulate saliva and register the taste, ensuring the cephalic phase is activated. |

The 20-30 Count: Your Starting Point

For the average mixed meal, aiming for 20 to 30 chews per bite is a practical and scientifically supported range to ensure you activate the cephalic phase, maximize amylase action, and slow your overall eating rate. This simple change is a powerful act of mindful eating.

Actionable Steps to Increase Your Chewing Count:

- Put the Utensil Down: After placing food in your mouth, place your fork or spoon completely down on the table.Do not pick it up until you have fully swallowed.

- Count to 10: Start with a conscious goal of counting to 10 chews for the next week, then increase to 15, then 20. Make it a game.

- Taste Register: Focus on the texture and flavor. When you slow down, you not only improve digestion but also experience a more enjoyable, satisfying meal, which further enhances satiety signals.

- Take Smaller Bites: A smaller bite is easier to chew thoroughly.

⚕️ A Simple Rx for Metabolic Health

In the complex landscape of modern health, it is easy to become overwhelmed by complicated diets and expensive supplements. Yet, one of the most powerful levers for metabolic control—the simple act of chewing—remains free, accessible, and often ignored.

By consciously adopting a higher chewing count, you are not just aiding mechanical digestion; you are sending a vital, preparatory signal to your pancreas, amplifying the release of beneficial gut hormones like GLP-1, and ultimately helping your body manage incoming glucose with grace and efficiency. This simple habit can be a cornerstone of a metabolic health strategy, helping to mitigate the detrimental effects of sharp post-meal blood sugar spikes.