SEO Summary:

- Raw spinach contains high levels of oxalic acid (oxalates), which bind to essential minerals like calcium and iron, preventing their absorption.

- Excessive raw spinach consumption can contribute to kidney stone formation in susceptible individuals.

- Light cooking, specifically steaming or sautéing, drastically reduces oxalate content and unlocks maximum nutritional benefit.

My Misunderstanding About the Mighty Green

For years, I believed that raw was always best, especially when it came to leafy greens. My smoothies were packed with raw spinach, and my salads were mountains of fresh leaves. I thought I was maximizing my nutrient intake, but I was accidentally hindering my body’s ability to absorb the very minerals I was seeking.

The truth is that spinach, while nutritionally magnificent, has a built-in defense mechanism—a chemical called oxalic acid, or oxalates. In its raw form, this compound acts as an anti-nutrient, effectively placing a lock on the vital calcium and iron that spinach contains. I realized that my obsession with convenience and ‘raw purity’ was causing me to miss out on the true benefits of this powerhouse vegetable.

I want to share the simple, non-destructive cooking technique I now use that instantly neutralizes this anti-nutrient, unlocking spinach’s full potential and ensuring my body actually absorbs the incredible iron and calcium it contains.

The Oxalate Trap: Locking Up Your Minerals

Oxalic acid is a naturally occurring compound found in many plants, with spinach being one of the highest sources. When we consume raw spinach, these oxalates enter the digestive tract and readily bind with positively charged minerals—specifically calcium, iron, and magnesium.

The Consequences of the Binding

- Mineral Malabsorption: The resulting compounds, like calcium oxalate, are nearly impossible for the human body to absorb. This means that while raw spinach contains high amounts of calcium and iron on paper, the bio-availability is extremely low. You’re eating the mineral, but your body isn’t getting it.

- Kidney Stone Risk: In susceptible individuals, excess oxalate consumption contributes directly to the formation of kidney stones (which are often calcium oxalate stones). If you have a history of kidney stones, limiting raw spinach and other high-oxalate foods is essential.

I came to understand that the goal isn’t just to eat nutrient-dense food; the goal is to eat food that is bio-available. And for spinach, that requires a little intervention.

The Solution: Light Cooking Unlocks the Vault

The good news is that oxalates are highly soluble in water and easily broken down by heat. This means a simple, light cooking method can drastically reduce the oxalate content and instantly free up the valuable minerals for absorption.

The Perfect Cooking Method: Steaming or Sautéing

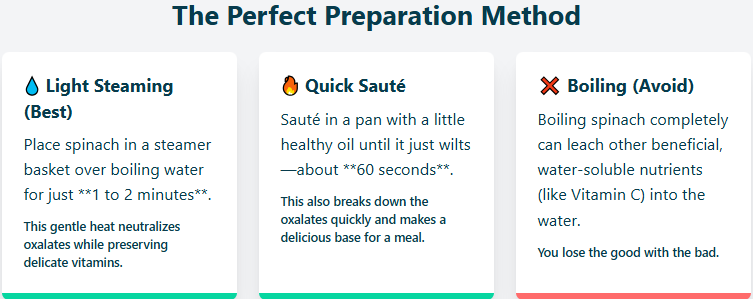

I avoid boiling spinach completely, as that can leach other beneficial, water-soluble nutrients. The best methods for neutralizing oxalates while preserving most other vitamins (like Vitamin C and folate) are light steaming or quick sautéing.

- Light Steaming: Place spinach in a steamer basket over boiling water for just 1 to 2 minutes. This is my preferred method. The gentle heat neutralizes the oxalates, and the steam doesn’t pull out the delicate vitamins. Drain immediately and serve.

- Quick Sauté: Sauté the spinach briefly in a pan with a small amount of healthy oil (like olive oil) until it just wilts—about 60 seconds. This also breaks down the oxalates quickly and makes a delicious base for any meal.

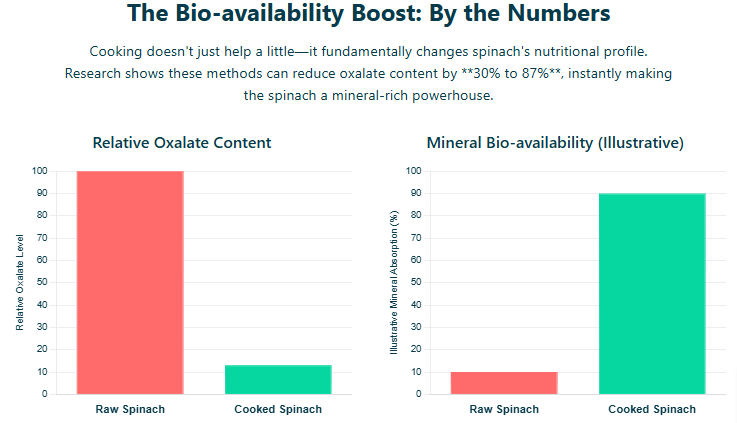

Research shows that these methods can reduce oxalate content by 30% to 87%, instantly making the spinach a mineral-rich powerhouse instead of an anti-nutrient drain.

My Personal Advice as a Health Advocate

My advice is not to fear spinach; it is to respect it. It remains an excellent source of Vitamin K, Vitamin A, and beneficial chlorophyll. But I now treat it the way I treat beans—as a food that requires proper preparation before consumption.

I still use a small handful of raw spinach in a smoothie occasionally, but I always pair it with a very high-calcium food (like yogurt or fortified milk) or a source of Vitamin C (like lemon juice). The idea is to give the oxalates something else to bind to besides the minerals I need to absorb.

However, for my daily intake, I now prioritize a massive volume of cooked spinach. It wilts down to almost nothing, making it easy to consume an entire cup of nutrient-dense, bio-available goodness—a feat that is impossible with raw spinach. I’ve found that this simple switch has improved my overall energy, likely because my body is finally absorbing the iron I was always trying to consume.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Does blending spinach in a smoothie reduce oxalates?

No. Blending simply breaks down the cell walls, releasing the oxalates, but it doesn’t neutralize them. The raw oxalates are still there and active.

Should I stop eating all high-oxalate foods?

No, most high-oxalate foods like beets, almonds, and rhubarb are otherwise highly nutritious. The key is moderation and focusing on light cooking for the highest sources, like spinach.

How does cooking affect the vitamins in spinach?

Some vitamins, like Vitamin C, are sensitive to heat and will slightly decrease. However, for a nutrient like Vitamin A (which is fat-soluble), cooking slightly increases its bio-availability. The tradeoff for better mineral absorption is worth it.

Is it safe to drink the liquid left over after steaming?

I advise against it. Since oxalates are water-soluble, much of the oxalate content will be concentrated in that steaming or cooking liquid. Discard it to ensure you remove those anti-nutrients.

Conclusion

The pursuit of health is often about finding the small, intelligent tweaks that yield massive results. My journey with spinach taught me that maximizing nutrition isn’t always about eating raw; sometimes, it’s about applying traditional wisdom through simple heat to unlock the food’s potential.

I urge you to make the simple switch from raw spinach salads to lightly steamed or sautéed spinach. By taking a mere minute or two to cook your greens, you are actively dismantling the anti-nutrient barrier, significantly increasing your body’s absorption of iron and calcium, and safeguarding your kidneys.

Sources:

Oxalate Content Reduction: Radek, M., & Savage, G. P. (2008). Oxalate Content of the Leaves of the New Zealand Spinach (Tetragonia tetragonoides). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 21(6), 555–558.

Mineral Bioavailability and Oxalates: Weaver, C. M., et al. (1997). Absorption of Calcium from Spinach in Young Adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(4), 1011–1015.